“I do love our adventures.” –Countess of Grantham (Cora Crawley) to Earl of Grantham (Robert Crawley)

“I do love our adventures.” –Countess of Grantham (Cora Crawley) to Earl of Grantham (Robert Crawley)

Last Monday I took advantage of two kids in school and one dental career on the backburner to hide out in a movie theatre and watch the Downton Abbey movie. My favourite way to see movies has always been solo (other than in a recliner-laden cinema with table service and The Husband), and weekday movies are gloriously empty. On this day, I shuffled in with my tub of popcorn just as the previews were beginning and sat amongst a dozen or so other patrons, all in an age bracket beyond my own, to watch the movie that was nearly four years coming.

I still remember watching the first episode of the show: it was the summer, one year after TH and I had moved from New York to Atlanta. I was three months pregnant, hot, uncomfortable, and nauseated. For an hour, the residents and servants of the Abbey took my mind off how much the first trimester sucked, and I was hooked for the next four years. Returning to the story after four more felt both novel and familiar, just like returning to New York feels now: things have changed, but the original heartbeat is still there. It still feels like home. Different, but home.

We are permanent residents of Australia now. This is not as…well, permanent as it sounds. We didn’t have to make a declaration that we would never leave (even though some days we feel ready to give that vow). Our citizenship in America holds fast and has not been transferred across the world. We get benefits like not having to pay for public school, and queuing in the non-tourist line at the airport. But mostly, the change is a symbolic one: we’re staying for at least two more years, and now we have the paperwork that solidifies that commitment. After our own side of the paperwork was submitted (including the documents ensuring the Australian government that The Kid would not unduly burden their coffers with his diagnosis), we were informed that a decision would be rendered in five business days. So we waited.

It was twelve business days, actually, and we felt every one of them. Our house in Atlanta in going through the final motions of its sale, and our furniture and books and other possessions are making their way onto a boat headed west any day now. What a cruel joke would it have been if we’d have had to scramble, houseless and couchless, back to America? I didn’t put it past God, who has pulled tricks like that before–upending my declared plans–and secretly TH and I wondered if we’d made the wrong call; if we weren’t meant to stay after all. The clock ticked, and I tried not to think about bulletproof backpacks.

Then a text came through on Friday morning from TH, full of Australian flags. And after that, we found out that, had we not been stalled by TK’s diagnosis–had we sailed through the PR process as quickly as it initially appeared we would–that the sale of our house in Atlanta would have hit us with a monumental tax burden to pay. It was almost like the whole thing was held up for a reason–a merciful reason that just felt hard at the time.

Turns out there was more to it. We just didn’t know.

Now, when we go back to America in December, it will be for a Christmas visit and not the return we planned on three years ago–the return that, when we moved to Australia, I was counting on for my own sanity and hope. That summer flight from Sydney to winter in America will be a round-trip one. We will go back to one home, then come back to another.

So much of life is about leaving, and returning.

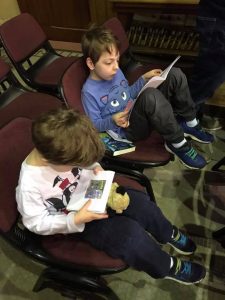

The boys are obsessed these days with photos of their younger selves. They pore over such pictures and bring them to me and TH, asking how old they were in each one. TK has taken to propping the frames up in various places: in front of his seat at the breakfast bar, against the window where he’s playing, alongside his pillow as he climbs into bed. They love going back, returning, to the people they used to be. I think they want to be reminded that their story has been going on for awhile now, that they have always been loved.

They go back to the same questions, over and over; the most frequent being “Why?”, along with queries about King Henry VIII and North Korea and Alexander Hamilton and duels. Their need for retellings, for repetition, for returns, is exhausting. And yet it establishes them and makes them feel at home.

We venture out to new places–the snow last month, the Great Barrier Reef soon–even as we plan returns to familiar yet changing ones. We return changed: more lines and wrinkles; long, skinny boy limbs that were, three years ago, short and chunky. We have more stories to tell. More words in our arsenal. Returned, but not a regression to speak of. Different, but home. Wherever we are.