We’re moving house, which is Australian for moving into a new house, in a couple of weeks. The change will be swift–two weeks to pack up our Aussie life and unpack it again–but not far, as we’re relocating to a street just across the road, a couple of minutes closer to The Kid’s school on a block where several classmates live. It was a property that The Husband and I gazed adoringly at on our phones. There’s a wine fridge. Still, it will be strange to say goodbye to the walls that welcomed us our first day here and have held us every day in the year since.

But, as I mentioned, there’s a wine fridge.

I will miss the balcony off our master bedroom, which, when my first friend here saw it, prompted her to exclaim what a great place it would be to drink wine. Then she faltered, asking if it was a bad sign that she associated wine with everything. I don’t remember how I assured her this wasn’t the case, but I remember thinking that we were perfect for each other and she was always welcome here. I thought about that the other day, as I sat on that balcony while TH bathed the boys down the hall, and the sun dipped below the horizon. I took it in: the view of the suburb beyond ours, the countless trees, the harbour, the boats. I took it all in and considered how a glass of wine, like a good rug, would really pull the moment together, but I was done with my quota for the evening, and then I wondered, like my friend, why I felt I needed the boozy add-on when there was already so much beauty. And for once, it wasn’t guilt or accusation that spoke first, but this idea: that this need to celebrate beauty as fully as possible, with all resources available, could be a gift. A thirst that is a sign of design, of the ever-present more that is just beyond our grasp.

I mean, I’ve had a lot of therapy, and we’ve ruled out alcoholism.

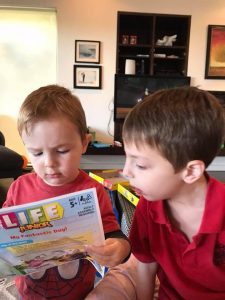

The Australians have another phrase I love: full-on. What I’ve gathered from context tells me that this means intense, unabated, complete. What an appropriate time in my life to learn it, as I’m pelted with hundreds of questions a day from two boys, one of whom is making up for four years of silence and it shows: “what if we don’t” and other contrarian positions constantly offered up for my explanation; discussions of the shape of brake lights and other conversations I never expected to have; and, perhaps most fraught and wonderful, questions about his special brain and entreaties to tell me its story again and again. We have identified so far that within his head lies an Apple operating system while his brother’s is an HP; that he hears sounds, and sees lights and the world, differently, and that, as he repeated to his therapist the other day, God gave him this special brain for a reason.

It’s a weighty responsibility, to provide the framework for a narrative that will so powerfully impact how he sees himself for years to come. It’s all the things: hard and awful and wonderful and not enough and too much. It’s full-on.

On Saturday the boys and I went to a birthday party that, between lunch and cake, included a disco room filled with lights, music, and a vaguely menacing life-sized plush monkey who doled out hugs and high-fives. Taylor Swift blasted from the speakers and my two–at turns shy and bold, serious and comical, all in their own ways–took to the dance floor without a second thought and began breaking it down, limbs flying, knees bouncing, heads bobbing. It was gorgeous. Then they pulled me with them, and I hesitated before noticing the other parents out there. In another life or locale or from a more commonplace cynical attitude I might have later identified the moment as absent of dignity, but what it actually lacked was fear. We partied alongside our children and it was unabashed and beautiful. It was full-on.

The next day we had the family of one of TK’s classmates come over for dinner, and the adults sat on the deck while the kids played. “Isn’t it so amazing that we get to live here?” the other mum, a lifelong resident of this suburb, observed, as we all stared across the harbour. Before their arrival I had taken my first Xanax in months because of my social anxiety and, in the moment there on the deck, I embraced the help of it rather than the guilt that is so often more readily available. I had sorted out dinner for eight people and I was actually relaxed. Minor miracle there, perhaps. Or, as the kids might call it, magic.

I’ll go with grace. Like the rain that began falling while we sat protected under a roof, or the wind and salt that had ripped through me on a solo trip earlier to the beachfront: nothing lacking. Full-on grace.