I remember the first few months of our time here in Sydney. When we walked off the plane in our winter clothes (pyjamas for the boys) into the stifling heat of summer, it felt as though we were landing in a vacation spot: the sun was shining down on us, the sea glittered ahead of us. Difficulties hit with less impact. Everything felt temporary.

Since then, our three planned years here have grown into five-and-a-half and a house and a dog and high school tours, and we are no longer camping/on vacation/temporary, or even permanent, residents by law, but citizens. Our annual rentals have given way to staying put in an owned property. And staying put, making a home, brings with it issues that are now, also, ours to own: no one else is going to show up to maintain the yard or seal the leaking shower or repair the flooded cinema.

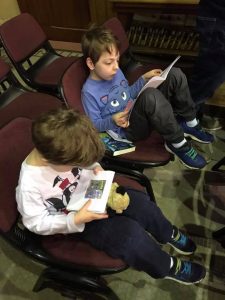

Being planted here, growing roots, inspires permanence, but it also reminds us that while our primary home is now in the Southern Hemisphere where Christmas will always be, wrongly, hot, we are still scattered, heart-wise, around the world. Cut to me clinging to the pieces of myself that reside elsewhere: watching videos of the boys in our first family home across the world, scanning broadway.com to recapture the feeling of living in the world’s cultural nexus, looking up the distances between London and other European cities for a currently unplanned introduction of the boys to that part of the world.

Home shifts. It bounces. And somehow it, in all its iterations, endures.

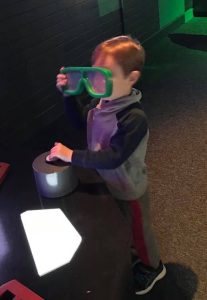

When we first arrived, I picked out all that reminded me of home: the red-headed friends who resembled my nieces; the burger takeaway that was similar to the one we ordered from back in Atlanta. Not replacements, but echoes. Now, the burger joint has closed and those redheads aren’t echoes but their own separate and enduring presence. The boys have more memories here than in the US. Warm Christmases may feel (gasp!) normal to them, the way small washing machines now do to me. White cheese dip is just not in the cards.

But oh, to be home, primarily at least, here. To have our routines, changeable by season but enduring by year. To spend that whole year, even winter, on the deck in the sun next to the dog who knows only this place, and us only in it. To know the people to whom we imagined saying goodbye after a trio of years as permanent fixtures who will never get rid of us. To be scattered, but to be somehow more for it.

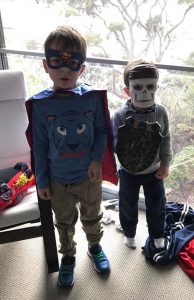

In one of her many masterpieces, this one called Advent, Fleming Rutledge writes, “the tourist can turn away in relief and go to lunch.” We are no longer tourists– we are home. We face the banalities and difficulties and triumphs of real life here (last night, because he had lost a tooth that day and was afraid that the Tooth Fairy would turn out to be the terrifying version he’d seen on Teen Titans, I finally told The Kid who she really was, and this morning before school he divulged the “secret” to one of his friends who of course already knew–I also dropped the bomb about the Easter Bunny but kept Santa magical…for now). This is where the boys will find out that Santa actually isn’t all that magical, where puberty will hit them, where The Husband and I will probably hit our midcentury marks. This is where life is.

And yet, being people of Advent, who live in that tension between the now and not yet, I’m at turns troubled by but ultimately grateful for the paradox of this form of life: the heart-scattering, the dual homelessness and deep sense of settledness. We are not tourists, not anymore, but this life is, when we admit it honestly, a bit fleeting in the overall scheme of things. Also in Advent, and Advent, I find that apocalypse doesn’t mean what I thought it did–it’s not some explosive, dramatic ending, but a slow and steady revealing, whether over a lifetime or throughout the span of time or in a single moment, joined to another and another until they all connect, these stepping stones leading always home.